You May Not Need Service Discovery

A consideration for distributed lifecycle tokens...

Image: JJ Ying

Image: JJ Ying

As modern application architecture is decoupled more and more into independently running services, we’re all once again experiencing the pains that some of us remember from the SOA days in the early 2000s. A popular saying in software engineering is that the two hardest problems in computer science are:

- Cache invalidation

- Naming things

…and then everyone typically adds a third problem, based on whatever particular stress they are going through at that very moment:

As of this year, my “number three” on the list is:

- Constantly having to remind myself that in-memory communication between software components is always easier than over the wire

My inner-voice is there to convince me that breaking a component off of the monolith (that component being what we are all calling a microservice now) probably introduces a range of new problems that can overshadow the original perceived value of decomposing the application in the first place. Even load-balanced monolithic application servers have SOA-like problems that are still there even if the monolith goes away. At MindTouch, we ran into one that had been hiding in plain sight for nearly a decade.

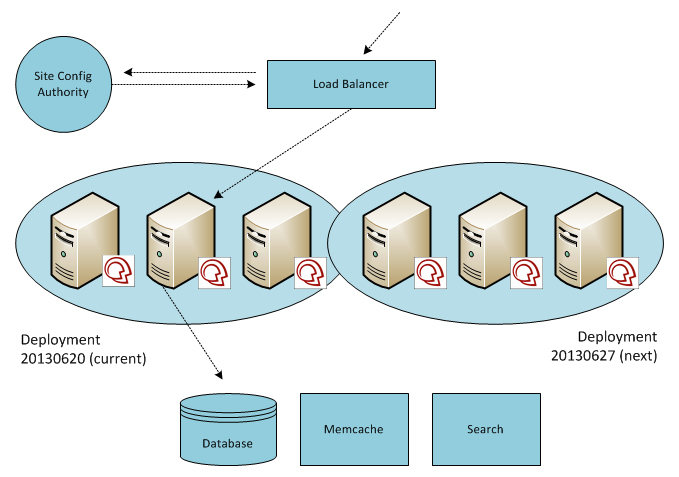

We’ve used a progressive blue-green deployment for many years to release new software on our shared, multi-tenant SaaS infrastructure. The approach is progressive in-so-far that tenants are switched to new software in batches (to monitor for problems and lessen their impact) as opposed to flipping a switch for all tenants at once.

Tenants are identified by hostname (ex: foo.mindtouch.us, bar.mindtouch.us, etc). Incoming requests are routed to the appropriate pool of EC2-hosted application servers for the requested tenant. If a blue-green deployment is in progress, and the tenant is queued to switch to the new software release but has not yet been moved over to it, the load balancer can still route correctly. This is due to the presence of a site configuration authority: a centralized database of all tenants and their deployments, plus an internal tenant manager application that writes to this database. Deployments are simply a list of EC2 IP addresses that represent the application servers in a particular pool.

1 | { |

Blue-green can certainly mitigate risk in this “load-balanced application server” architecture. Any software update, regardless of whatever model or methodology you use, will always introduce risk. This particular approach makes it tolerable for us and our users. Due to the requirements that we had when standing up this infrastructure, we chose HAProxy over Amazon’s native load balancer. This meant that while we could place these application servers in auto-scaling groups, there wouldn’t be any benefit if our load balancer of choice and our home-grown deployment model couldn’t take advantage of it. If our service ever came under heavy load, we would have to spin-up EC2s manually, provision them with all the requirements to run our software (and install the application software itself) using Puppet, then add the EC2 IP address to the application server pool for the live deployment. Historically, this was required so infrequently that automating these steps didn’t seem necessary.

Until we had a real SaaS business going…

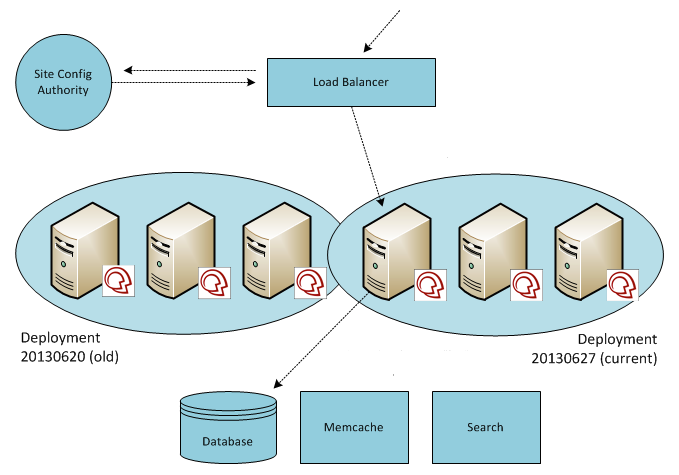

This year we completed a migration of all application servers and event-driven microservices to containers hosted on Amazon EKS (k8s). The many reasons behind the switch are deserving of a case study, but the key point that’s relevant to this post is that we could quickly auto-scale application servers (now in k8s pods) and it was becoming necessary to do so. As an added benefit, all load balancing between deployments could be managed within k8s, making the old deployment model of static IP address lists obsolete.

There was one big problem. The fore-mentioned internal tenant manager can restart tenants - which is required for certain kinds of configuration changes. Each application server, in every container, keeps an in-memory record of the configurations for every tenant that it’s had to serve. Keeping an in-memory copy allows any application server to quickly handle a request for any tenant (so specific tenants need not be pegged to specific containers). In order to restart a tenant, the tenant manager would send a restart HTTP payload to an internal API endpoint on each application server. With k8s managing and auto-scaling all containers, this application had no idea which IP addresses to target - effectively breaking this capability.

We need service discovery!

The faulty assumption, out of the gate, is that this tenant manager still needs to know where the downstream application is running. When faced with challenges, we can often gravitate towards what is known or what we are comfortable with. We presume that other options are going to be difficult to achieve. Why not? We obviously chose the simplest option when we first built this! With that presumption in place, we are likely ignoring an even simpler and possibly more elegant solution - because in the last few years we’ve become smarter and better at our craft.

All the tenant manager needs to know about is one location: where to write a big message on the side of a wall for someone to read later. The message is for any application server that reads it to restart a specific tenant - and every application server knows to check the wall before handling an incoming request, just in case there is new information about the intended tenant for the request. We implemented this with a distributed lifecycle token.

A distributed lifecycle token is an arbitrary value stored in an authoritative location that downstream applications and services can use to detect upstream changes. If downstream components store the value of the token and later detect that their stored value no longer matches the authoritative source, they can infer some sort of meaning from that. In our use case, they know that the tenant manager has requested the restart of a tenant. Allowing downstream components to eventually take action on, or be triggered by, a write to a data store, an event stream, or a similar authoritative location is a great example of event-driven and reactive programming in use.

First, we need a connection to a centralized, in-memory data store (such as Memcached, Redis, etc.) that can be accessed by any application server. Any tokens in this data store need to contain some sort of tenant-specific context. The following example is not meant to be representative of a full-featured Memcached client, but rather the minimum required to demonstrate this implementation.

1 | public class MemcachedClient : IMemcachedClient { |

Next, we have libraries that manage the initialization and fetching of tokens using our tenant-contextual Memcached client.

1 | public interface IDistributedTokenProvider { |

Next, we wrap our general-purpose distributed token logic in an easy to call utility. We can use this both in the tenant manager as well as the downstream application servers.

1 | public class TenantLifecycleTokenProvider { |

Instead of sending an HTTP payload to different IP addresses in a pool of application servers, now the tenant manager simply does this:

1 | var tenantId = '12345'; |

A downstream application server, when it handles an incoming request for a tenant, first checks if it can lookup an in-memory copy of the tenant’s configuration. If not, it fetches it from the site configuration authority and looks up the tenant’s lifecycle token. If the lifecycle token for this tenant is not yet initialized (it may not have been if the tenant manager didn’t need to restart the tenant), then the application server initialize it, so that other application servers in the pool can know the current lifecycle state of the tenant.

1 | var tenantId = '12345'; |

When handling an incoming request, the application server checks if the tenant needs to be restarted before fulfilling the request. If the distributed lifecycle token has changed since we last read it and no longer matches the tenant’s lifecycle token, we know that the tenant manager is asking for a tenant restart.

1 | var tenantId = '12345'; |

In our particular architecture, nullifying the tenant at this stage triggers the application server to instantiate a new Tenant object and register it in the lookup, as seen above. This process is repeated for all application servers. The addition or reduction of containers or pods does not affect the tenant manager’s ability to restart tenants.

I am absolutely not a critic of service discovery in principal. When necessary to facilitate direct communication with components on a network, it can be a life-saver. However, if your use case does not require direct communication and eventual consistency among downstream data, and application state is acceptable for your use case, consider reactive programming solutions. Everything will be ok (eventually)!

…and if it’s not, you can always deploy systems to handle those situations out-of-band: